a numbers game: the reality of the wnbl pathway

For many players, the state league season is imbued with a sense of hope. It is an audition for the national league. But there is no point in auditioning if there are no available positions.

I began to write an essay almost two years ago, when I was first signed to an AFLW team. It was a long, meandering piece: alternatively emotive and clinical; part memoir, part research, part critique.

I never published it in its entirety. Instead, it became three separate articles:

No Capital

A Myth of Progress

The Fallacy of the WNBL Development Player

There were mixed reviews.

This is the original essay’s fourth and final incarnation, focusing on the junior into professional basketball pathway.

It uses data on the pathway of every athlete who was rostered for the 2023-24 WNBL season.

There is a clear, simple process to reach Australia’s national basketball leagues.

In the state of Victoria, specifically in its area classified as metropolitan, it begins with many young children playing basketball, usually on a Saturday morning.

Some of these children are then selected for representative teams that compete on Friday nights. From these teams, a portion of children are selected for high performance programs — the Future Development Program (FDP)1, the State Development Program (SDP) or, for a slightly older child identified as having the potential to represent the country nationally, the National Performance Program (NPP).

From this portion of athletes, the coveted state teams are chosen. These operate at Under-16, Under-18 and Under-20 level2 and, every year, the High Performance Selectors of each age group whittle the numbers away through weeks of tryouts before selecting fifteen children out of hundreds of athletes. Although any player can be nominated by their association to tryout, a Victorian state squad consists almost without exception of children who are already inside the high performance programs.

From the fifteen children, ten are taken to the National Championships, where they compete against the ten children from each of the other states.

Basketball Australia then selects a fraction of these players, across all states, to tryout for its junior national squads. These squads, at Under-17 and Under-19 level3, represent Australia at international tournaments.

Out of these squads, an even smaller fraction are offered scholarships to the Centre of Excellence (CoE) program at the Australian Institute of Sport (AIS) and promptly move to Canberra to finish high school and to train.

Victoria has, historically, been accepted as the strongest sporting state so by its Under-20 state team tryouts, many of its athletes are children automatically chosen from the CoE.

The talent identification process can be likened to an escalator.

It is more accessible to step on early, at the bottom, when a child is younger. The passage is an expensive one, because the camps and promotional jamborees and elite invitational tournaments all have fees attached, but the cost is necessary if a child is ambitious for a professional basketball career in this country.

A child whose parents have not, by the age of twelve, paid for them to attend one of the Talent Identification and Player Development Camps is unlikely to be invited to tryout for the Under-14 or Under-15 Southern Cross Challenge. A child who does not attend the Southern Cross Challenges has a lower chance to be selected for the Under-16 East Coast Challenge. A child who does not go to the Under-16 East Coast Challenge does not make the Under-16 Victorian State team. A child who does not make the Under-16 Victorian State team will struggle to make the Under-18 East Coast Challenge, and will consequently not make the Under-18 Victorian State team.

A child who is never chosen for a state team, and consequently is never able to compete at the Nationals, does not receive the incidental opportunity to trial for a scholarship to the CoE.

A child who does not come out of the CoE is less likely to achieve a career in Australia’s professional basketball leagues.

Are you new here? Take the new reader survey.

The Centre of Excellence describes itself as being ‘the world-leading junior development program since 1981.’4 Its graduates, after completing high school and their basketball scholarship, sometimes elect to go overseas to college in America, but a large portion — especially historically — have been discouraged from any option other than moving immediately into the local professional competition.

The CoE is ‘dedicated to the development of future Boomers and Opals’ which means, theoretically, these carefully chosen athletes must be the next crop. Their potential has already been verified numerous times throughout their childhood by state teams and international tournaments so it is easy for even a WNBL coach, who has a limited roster, to spend a position on them.

This is a condensed explanation. There are always deviations5, but otherwise it is systematic.

‘A child whose parents have not, by the age of twelve, paid for them to attend one of the Talent Identification and Player Development Camps … is less likely to achieve a career in Australia’s professional basketball leagues.’

The WNBL is made up of eight teams.

Each playing roster is required to have a minimum of ten contracted athletes, and a maximum of eleven — including amateur players who, to retain their college eligibility, do not need to be paid the minimum wage. Not every club signs eleven which means each season there are, generally, 85 available contracted positions, league-wide.

But two of those positions, per team, can be reserved for international import players, usually Americans. That means there are actually only about 69 contracted positions available.

New Zealand players do not count as imports, and they sprinkle throughout the league so maybe there are more like 64 available positions.

There are probably an equivalent number of naturalised Americans. For the calculation, pretend there is only one: 63 positions.

Three marquee athletes combine with the imports to make up each of the eight team’s starting five — these three are, relatively consistently, CoE alumni, ranging from five years to over a decade since graduation. Removing them, there are about 40 available positions.

Coaches usually try to form their roster with at least a strong seven, so the two athletes who come off the bench first are also, relatively consistently, CoE alumni: maybe slightly younger or, conversely, athletes deeper into their career. Assuming there are fifteen or so means 25 available positions.

The eighth and ninth spots are regularly filled with established athletes who, though not studying officially at the CoE, were part of junior national squads trialling for international tournaments. This roughly leaves 9 positions remaining.

The tenth or sometimes eleventh positions are known to be divided between athletes who are referred to, informally, as not having a name. They have minimal basketball status. They did not represent the country as a child. It is likely they do not have a parent or family member who played professional sport. They, instead, might have returned from a convincing college career in America — or worked through their local national league club’s system until they were, especially in non-Melbourne teams, elevated from being a Development Player. They are still athletes who at least made a state team. There might be three who did not.

Out of eight teams, that leaves barely a handful of potential positions for players who were not products of the junior system.

There are ten girls per state, per age group, making a state basketball team each year in this country.

Out of them, Basketball Australia gives out approximately three to five scholarships to the CoE program. The number is discretionary: BA welcomed two new scholarship athletes for its 2020 CoE women’s program6, six for 20217, four for 20228, three for 20239, and three for 202410.

As of May 2024, BA’s website cites 26 athletes currently at the Centre: 12 girls and 14 boys11.

It is estimated there are around 450,000 girls and women playing basketball in Australia12. Their involvement ranges from social to domestic to elite junior, youth and senior leagues.

The NBL1, owned by the NBL, is the reserves-equivalent to the national league and fields both a women’s and men’s competition. With 74 clubs, it boasts:

‘145 teams featuring over 2,000 players in men’s and women’s competitions.’13

That is maybe 800 elite female basketballers combined with, conservatively, 100,000 girl athletes.

Similarly, there are just under 600,000 girls and women playing AFLW in Australia14. These players also range from local to professional. The VFLW — football’s NBL1-equivalent, a tier below the AFLW — has 14 teams. Approximating list sizes to thirty, that amounts to 420 elite female footballers.

For two sporting codes, that is a similar level of participation; there are more girls playing football at any level, but there are more women playing basketball at a level just below professional.

The difference, consequently, is in the incongruence of opportunity.

The WNBL was founded in 1981 with nine teams15. By 1989, there were thirteen.16 From 1998 to 2007 there were eight. The number fluctuated between and up to a maximum of ten until 201617 — when it returned to, and has remained at, eight.

Eight teams means there are currently, at maximum, 72 available contracted positions for Australian athletes in Australian professional women’s basketball.

Conversely, the AFLW was founded almost four decades later in 201718 with eight teams. By 2020, there were fourteen. Currently, there are eighteen.

Eighteen teams means there are — even removing around 36 positions for international players19 — over 500 available contracted positions in Australian professional women’s football.

Data of 2023-24 WNBL Athletes

on pathways

I could not find any statistics on pathways into the WNBL, so I tried to find them, then compile them.

Money is used as one of the reasons the WNBL has, for almost a decade, not only not attempted but resisted more expansion attempts.

Caretakers have been worried about the financial safety and overall sustainability of the league.

The caution seems sensible: women’s sport in 2024, despite standing on decades of tireless advocacy for progress, continues to face challenges; the WNBL was formed in a time when women participating in activity, let alone professional sport, endured even greater opposition and misogyny. There were profound repercussions if it did not succeed.

Any choice, including on number of teams, directly impacted the longevity of women’s professional basketball. This is still true — any decision made by leaders for an organisation has impact — but lack of decisions have impact too.

‘The WNBL, and more specifically Basketball Australia’s ownership of the WNBL, prioritises stability. Stability does not necessarily connote safety … to refuse change sometimes means to greatly limit your ability to survive.’

The fiscal argument is used publicly. The less overt reason used to parry expansion is a lack of talent.

It is claimed there is not enough talent — meaning adept players — to form more teams. Any expansion would dilute the league. The quality of the product would be reduced.

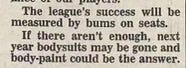

The excuse reflects a quiet, surreptitious opinion: the WNBL is successful not in spite of but because of its lack of opportunity.

It forms off two beliefs, separated marginally by nuance, that have been wielded against players, interminably, by the highest levels of authority. There should be no rush to expand, one counsels. The league is a financial risk as it is. You should be grateful any interest still remains in keeping it.

The other is more placating. The league will grow, it insists, it’s on the cards, it’s been on the cards, the cards take a while to prepare, we can’t actually show you any preparations so just trust they’re happening — but, also, if nothing changes, that would still be good, that might even be for the best. It means the league means more. It means you mean more. We are exclusive. Prestigious. Our players are the best of the best.

Other women’s sporting leagues have shown what expansion, with strategy and pathway investment, can do for all female athletes.

From a myriad of reports, genuine change is coming to the WNBL. Investors, private ownership, new directions, more teams. The biggest challenge the WNBL will face will be inspecting, and then understanding, who it is and who it wants to be.

‘There is no longer any distinguished, cultural identity in simply being a woman’s sport; more leagues exist and these leagues are also women’s sport and they have specific characterisation. They have their own branding, inclusive to but not reliant on their gender. Women’s basketball needs to be given, or allowed to find, a soul.’

I assume a significant portion of the little girls and young women playing basketball in this country aspire to the national league.

I am not contending anywhere close to that number should, or could, be a professional basketballer. But I do suggest that a substantial percentage would not become one even if they did have the potential. The metaphorical funnel — the elite basketball pathway — narrows so early and so drastically it becomes almost linear.

The NBL1 is a competition that is marketed, sponsored, broadcasted on television, and affords a wage to many of its players. It is a state league that, with annual championship tournaments, creeps onto the national stage.

Its athletes have traversed different paths to reach it. There are many who have not made their state’s junior teams, who have not participated on junior international tours, who have not graduated from the CoE. The NBL1 has firm access to grassroots associations. Its teams are, often, a pinnacle of them. The competition is a visible, and accessible pathway, from junior sport to elite competition.

But that pathway ends there. It is not consolidated with the highest level. Because there are very few, if any, of those athletes unaccompanied by status from their junior sporting career who make it into the WNBL.

The state league is positioned as the way for an athlete who has not graduated from the CoE, and is not a Development Player, to work into the WNBL. But similar to the DP pathway, the correlation between the NBL1 and the WNBL is an illusion. For most clubs, there is no relationship between the two.

The state league season is imbued with a sense of hope and resolve for many players who, in good faith, treat it like an audition for the national league. But there is no point in auditioning if there are no available positions.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to thist to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.