i have a few questions: on ethics, habit and all those likes

I would rather watch pornography—created ethically—with my family than scenes of violence. The order of the em dash has never been more important.

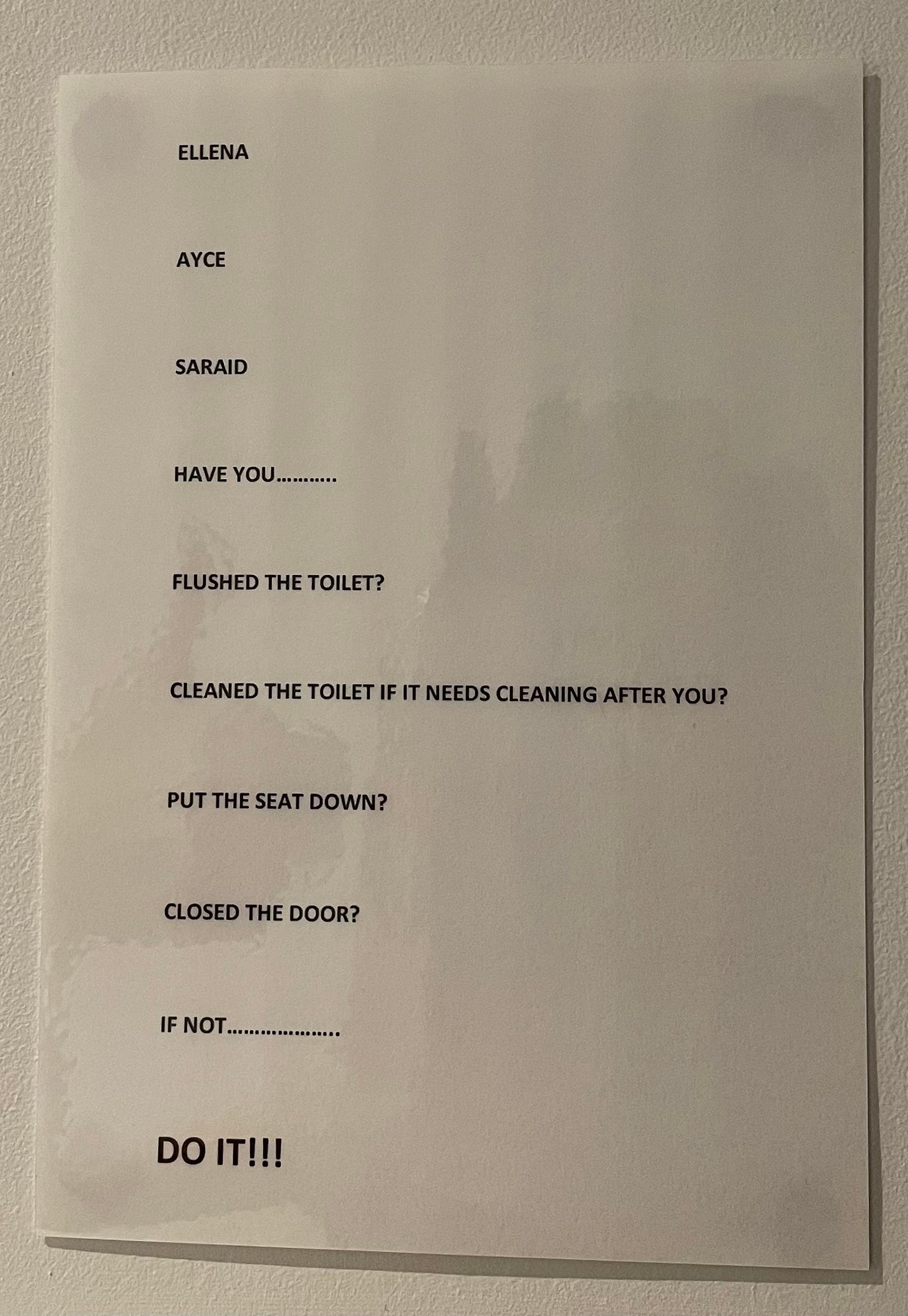

At twenty-six, I live at home with my family.

My family consists of a dog, two cats, my parents, and my two adult siblings. Our lives together, in the house, maintains the steady, tugging sense of time passing and also, simultaneously, of it having been stilled. The three kids each sleep in our childhood bedrooms, pull food from the same fridge we have for decades, sit on the couch at night with our parents when we are home at the same time and watch television together.

During the months that combined into years of state-wide lockdown, we chewed through a lot of television. Episode after episode, series after series, curled inside blankets through winter, strewn with the windows open and bowls of ice-cream in our laps during summer. The dog snored from his place on the couch. We assembled around him in positions we squabbled over until they became too established by routine.

It was a treasured time; familial bliss. We rarely went a night without observing a theatrical portrayal of intercourse.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to thist to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.